By Chris Ramsay: Secretary-General, Chief Herald

If you are a fan of the award-winning historical drama on the life of the late and great Elizabeth II, you have come to the wrong place. As enticing as it has been to see a reenactment of the trials and tribulations of representing the crown, we will instead be looking more closely at what the crown represents—in particular, that, or should I say those, of Austenasia.

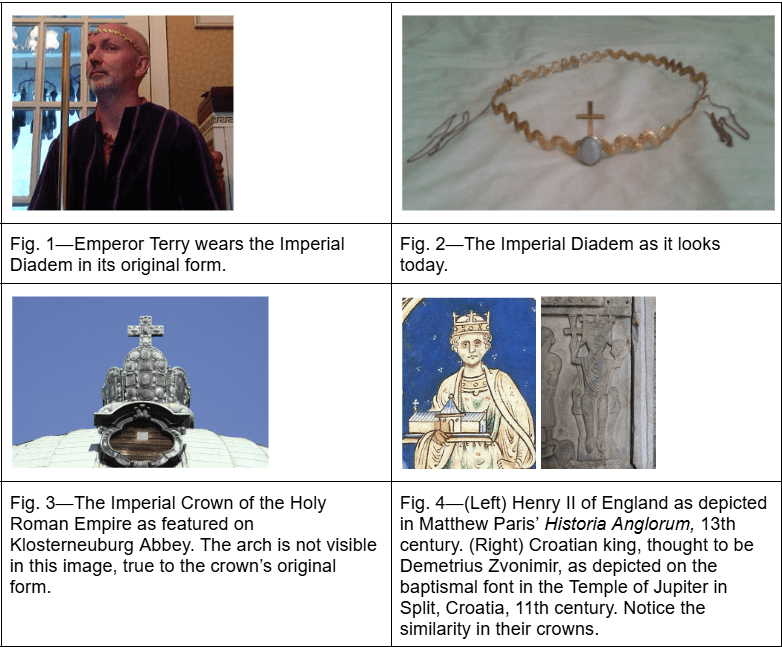

The Imperial Diadem made its debut in the spring of 2009, when it was constructed for the coronation of Emperor Terry. At this point, it consisted of a golden ribbon wired in a circlet and sporting an unspecified white stone, informing a front and centre of the crown. The stone is a family heirloom of the Austens, and indeed the comparatively modest symbols of imperial potency remain in the possession of the house (fig. 1).

The diadem was modeled after those of later Roman emperors, which to begin with, were informed by the trends of archaic Greek diadems. Older Hellenic traditions, along with Persian and Macedonian traditions appear to have established a new meta in the immediate post-Alexandrian orient. The clue is indeed in the name, which denotes a type of headband worn by rulers, aristocrats, and occasionally victorious athletes. In this understanding, it is much like its popular cousin, the laurel crown; both developing into circlets made out of metal, instead of organic material. The diadem’s other relative, the eastern crown, is ubiquitous in subsequent roman symbolism, and by now it begins to embody those aspects of a crown we consider absolutely quintessential today. If you can get your baby cousin off the iPad for just a moment, ask him to draw a crown. If he has yet developed hand-eye coordination which satisfies elsewhere to YouTube reels, it is most certainly the eastern crown he will draw. Roman emperors saved the eastern crown for esteemed deities, and tended to prefer diadems.

Later in 2009, pendilia were attached on either side of the Imperial Diadem in a fashion reminiscent of Byzantine trends from the early middle ages. The Holy Crown of Hungary, a near thousand year old artifact that has yet to be retired, features five pendilia—two on either side, and one in the back. In addition to being one of the oldest surviving crowns in the world, it is a stellar example of Byzantine craftsmanship and the contemporary design preference which has also made its impact on Austenasian regalia. A crude 2010 drawing of Emperor Terry depicts the Imperial Diadem as it were then.

In 2016, following five years since the reception of Emperor Jonathan into the Orthodox Church, he had a cross attached to the front and center of the crown where it remains (fig. 2). Not only is it a simple, symbolic and stylish amendment to the crown, but if we resume our navigation through the middle ages, it appears to be in line with subsequent tropes. Crowns tended to be open, that is to say, without arches. Although it did prominently occur throughout the early and high middle ages, arches did not become the meta until the late middle ages. It has been said that arches were popularised by Emperor Charles V himself, and that is believable, because by the time of the early modern period, it had become the standard. An early example of a closed (arched) crown is that of the Holy Roman Empire, which features a single arch going across the top, ending at the base of a cross front and centre. The arch is courtesy of Emperor Conrad II, however, when it first debuted at the coronation of Emperor Otto I, the arch had yet to come (fig. 3). In contemporary art, the crown of choice was open. No longer resembling classical diadems, but decorated along the edges with trifolia, fleurs de lis, or a cross front and centre, if not all around (fig. 4).

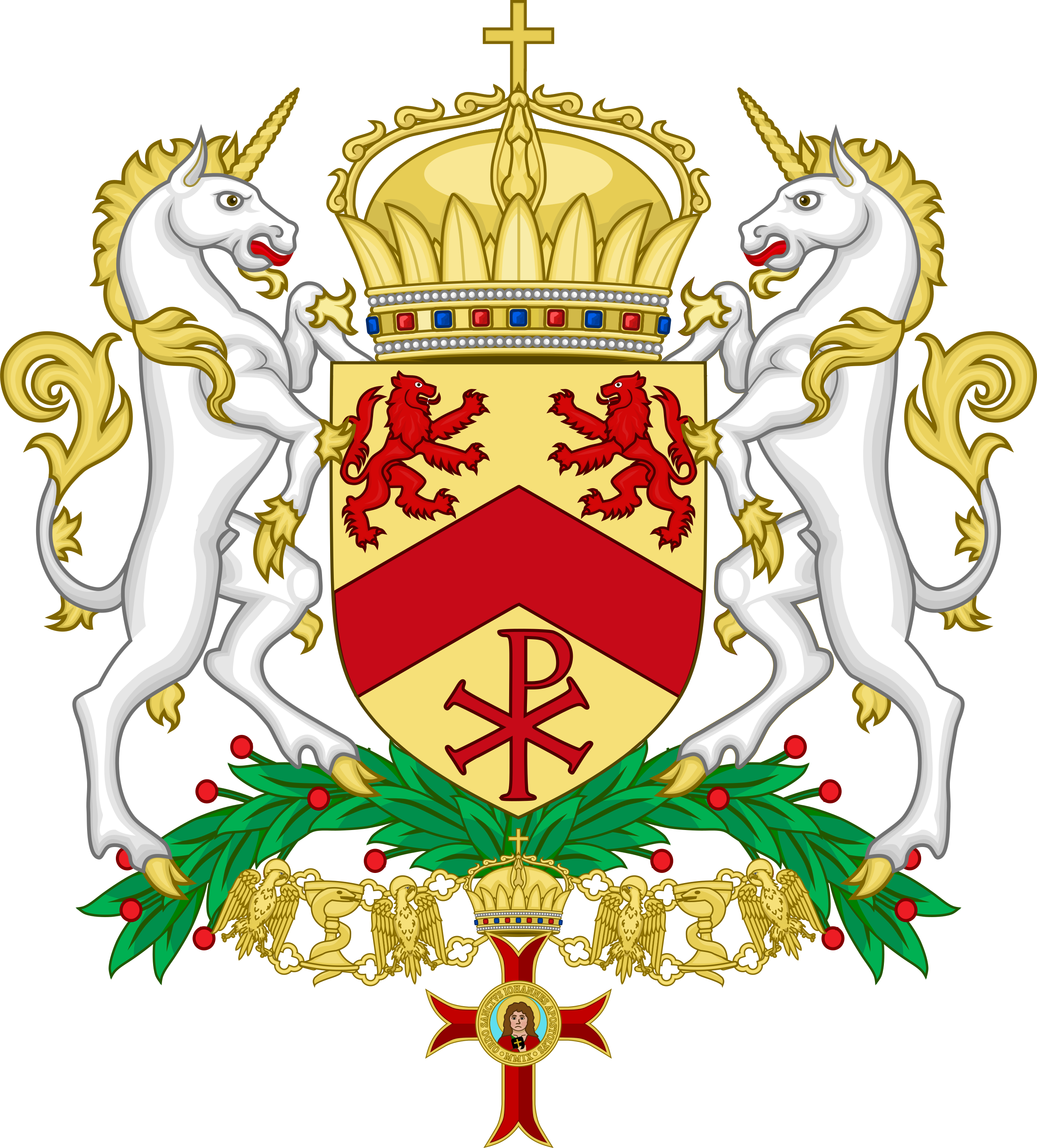

Keen-eyed observers will have noticed that the Imperial Diadem does not much resemble the crown which sits atop the coat of arms. Likewise to how crowns were portrayed in medieval art it does not necessarily resemble the actual regalia which would have been worn. This may have been because the artist endeavours to depict kingship more generally, or has no access to reliable depictions of the regalia. Conversely, we see in early modern portraiture for example, that crowns are depicted as faithfully as possible, emphasizing the symbolic value of that crown in particular, as opposed to the mere concept it embodies. The British and Dutch crowns are still depicted with substantial likeness to the original copies. Nowadays it is not uncommon for crowns, particularly in heraldry and heraldic logotypes, to be entirely removed from their real life counterparts. The evolution of the crown’s design has reached an end point, but the manner of its depiction and use has not.

On the 4th of April 2025, this spring, the coat of arms of Austenasia had its first change in 14 years, to identify the reign of Emperor Aggelos. Notably, it had featured no crown at all, but a laurel wreath in reference to those worn by parading imperators of the Roman Republic, exemplary athletes, and Rome’s subsequent emperors. The new heraldic crown is true to both modern and ancient standards, and is riddled with imperial tropes.

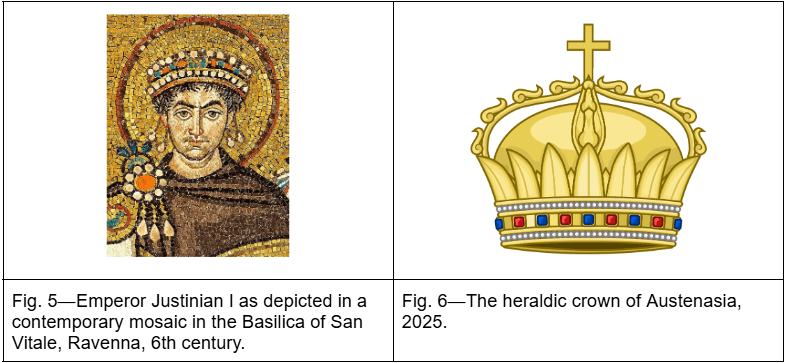

The base of the crown is borrowed from the diadem depicted on an iconic mosaic of Emperor Justinian I (fig. 5). Rays emanate from around the crown, in the fashion of an eastern crown—a memetic accessory broadly afforded to any conception of divinity, kingship, and virtue spanning several religions and empires, particularly in the near east. Instead of a cap of maintenance, a semi-orb traces the inside of the crown. An early form of the mitre may have inspired Byzantine jewellers to do something similar, as can be seen in the crown of Holy Roman Empress Constance of Aragon among other examples. In cases of closed crowns lined with fabric on the inside, low-down arches served more of an active role in its structural integrity. Tall arches, however, adorn the heraldic crown of Austenasia. Not for structural reasons anymore, but for the same aesthetic reasons that pleased Emperor Charles V and his later admirers—on which he would use what looks like golden curls, called flourishes, instead of pearls and stones. On the top is a plain latin cross (fig. 6).

From a humble diadem designed with initially unexplained, yet very noticeable inspirations—as those which developed after Alexander the Great, and to alternate depictions of a tall and massive piece of insignia—such as those we know today. The fashion of imperial and royal headgear can hardly be classified as an entirely linear development. It can be said that crowns of Hellenic and Roman precedence have nevertheless influenced the fate of the crown in general. And to a comparable extent, that the crown of Austenasia has inadvertently gone through a similar evolution to that of the crown as a whole.

Leave a comment